Major (Ret’d) Chandra B. Gurung

Major (Ret’d) Chandra Bahadur Gurung

(Portrait © Gurkha Voices Oral History Project)

-

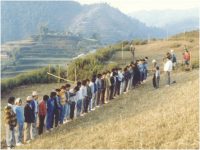

The Galla Wala visits village

-

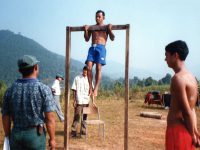

Recruitment test - 65 pull ups!

-

Village water supply (Earthducation MT Lab)

-

Routine recruitment tests

-

The times hill running test during recuitment

-

Houses similar to Chandra's village

-

Audio 1

-

Audio 2

-

Audio 3

Upon retiring from the army Chandra Gurung works as a Welfare Officer for the Gurkha Welfare Trust. Chandra was selected as a Gurkha Major and before that he served Her Majesty the Queen in Buckingham Palace as one of the two Queen’s Gurkha Orderly Officers. Chandra’s interview audio extracts are accompanied by the transcript below.

Colchester’s 308 Air Cadets have made a short film with the Gurkhas which can be viewed by clicking on here.

(More veteran stories are in our book, published later this year. Keep posted via our blog: www.gurkhastories.wordpress.com)

Audio 1 (1 min 40 secs)

… It was very, very hardship in the village. My family was not well off but in the village standard, by village standard, we are sort of upper lower class or in a middle class family. So we did not face much hardship, but the other people, most, the majority of the people, ninety percent of the villagers, I mean, we didn’t see any cash in those days because, I mean, there was no trade. Only means of getting cash was either you sell your livestock or your grains, or if there is someone in the army, Indian Army and British Army, they will bring a little bit of money. And it was very hard in the village. But again, it was very sort of–, I remember–, I mean, the only time we needed money was during the festive times, when you had to buy clothings and you didn’t have any means of communication, no telecommunication, no lights, I mean, no cars, etc. Actually you didn’t need money. And there were no hospitals and no pharmacies at all. If you got sick, tough. You go to the witch doctor or something like that. To take the sick person to a medical centre or the hospital was out of way because it was two, three days carried in a basket, etc. So people just died.

Audio 2 (3 mins 27 secs)

[It was a] sort of tradition in the village. Whenever you are able to, able bodied, if you can, nearly all the boys in the village did try to join the army. Not only British Army, Indian Gurkhas as well. So there was the opportunity, while I’m still in college, there was the opportunity to join the British Army. In those days it was 1974. What happened in those days was we called Gallah, who is sort of recruiter. And they would go round the village and line up the boys and take measurements, height, weight, chest measurement. And you can see by looking at them and you are in your shorts, so naked, and then you stand up and the recruiter can see whether the boy is suitable or not, and then he would select.

If there were nine vacancies for him, he would select double the number and then take them down to one of the depots, the British Gurkha depots, in Nepal, and then give you to the camp, hand it over to the camp. And there were other recruiters in the camp, who were–, some of them were serving officers, British officers, Gurkha officers, other ranks, who would make the selection, medical, etc. And it was a very interesting time in those days because up in the village you would have not seen any army barracks. Forget about the army discipline, etc. You are just lined up in the morning, a bit of breakfast, bread and tea, then go to the selection board. Sometimes you’re running, sometimes chest measurements, sometimes weight, sometimes medical, sometimes a little bit of interview, and then just paperworks.

Filtering, say, if there were five hundred vacancies, they would bring one thousand candidates, potential recruits, and then gradually they would filter down those who were not suitable, those who were shorter or chest is not enough or can’t walk properly. It’s very strange. I mean, the walking in the flat plains, when you are just walking up and down in the villages, you come down. It’s bizarre. Tell the boy to walk straight in the flat ground, you will notice completely [laughs]–, it was so difficult for us. And running was different. We could run uphill, downhill, nice and easily, but running in the flat ground was different, difficult. And it was a very interesting day was the final result. You wouldn’t know and everybody was lined up, two, three lines, and the officer, with his–, we had all the chest numbers, blue ink, [points across his chest] throughout the selection process. And then they would call the number, those successful ones, and run a hundred metre dash [laughs] to that point and then that’s it. And then paraded, taken down to Hong Kong.

Audio 3 (2 mins 20 secs)

But the excitement was in the second time when I was selected, when my number was called in [laughs]. That’s a big excitement.

My father was not very interested, but he never said me not join the army. My mother was pretty interested and she would look up to it. She might have been excited. But I didn’t see them for the next three years, as soon as I joined the army, in Nepal as well, because we were not allowed to go back home. The depot, British Gurkha depot, was down in the plains, south, about one day’s travel by bus, so it’s about six hours’ bus journey down in the south, near the Indian border.

It was normal for the Gurkhas in those days, because we were not allowed to. There was no freedom–, well, not freedom. I mean, it was a military–, British Gurkha ruling was that once you joined the army your next leave was after three years, or two and a half years. There was reasons behind that as well. I mean, one maybe sanctioned rule. The other was because in those days–, not in our days but before 1965 there was no direct air link to Nepal from Malaysia. Mainly Gurkhas were serving in Hong Kong, Malaysia, mainly, so they had to sail, before 1965, they had to sail, it would take seven days, and come to India by train to one of the British Gurkha depots in India, then to Nepalese border, then further six, seven days’ walk to your home. So that was the reason, could have been the reason, because it took at least a month one way to come home and one month to go back and report back to the battalion. So you got four months’ free leave in full at home. So that could be the reason. So maybe the army couldn’t afford to send everyone every year on leave. That could have been.

The day I came to England, I came here with that money, etc. I mean, you had to mortgage a house, start from the bottom. You buy teacups, teaspoons to fridge, freezer, house, carpet, bed, television, internet, etc. All that money just disappeared.

Oral histories: © Gurkha Voices Oral History Project